Superheroes. Or, well, superpeople, in any case. Capes. Zombies. Whatever. It had never crossed my mind that I’d be one of them someday, mostly because it was a morbid thing to aspire to.

My head was spinning. I couldn’t quite rationalize everything I was feeling. I couldn’t quite verbalize everything I was thinking. How could I describe a sort of grief that was directed at myself?

Easier to bring my mind back to the present. Easier to be distracted, in some way. In any way.

In addition to the canon storylines on this website, The New Ars Moriendi can be used as a setting for Cortex Prime. It’s a contemporary world with the twist of superpowers that don’t bother pretending to be more science than magic. When an interesting enough person dies for the first time in this setting, the current stand-in for Death challenges them to pick and play a game, then uses the information that comes to light over the course of the meeting as inspiration when he resurrects them with a superpower or two. Why? Well, because he wants to see what happens.

Each person revived with powers is already going to be on their way to heroics or villainy — the powers just push them to superheroics or supervillainy. To an extent, this conflict is engineered on purpose. When the heroes have the upper hand, more villains emerge, and vice versa. It wouldn’t do for one side to win in the long run, after all. There’d be no new stories if that happened, and new stories are interesting.

In this game, you create a character by assigning attribute dice, defining distinctions, and picking a few specialties. Once you’ve got your interesting character, you decide how they die. Then, pick a game (any will do) and explain what your character’s strategy in Death’s lobby is. The GM will use that info to create your power for you. As you play, you’ll be able to call on your past experiences to propel your journey forward and improve various aspects of your character to reflect their transition from normal person to superhero (or supervillain).

- Genre and Tropes

- What You Need To Play

- Character Creation

- Growing Characters

- GMCs

- Running The New Ars Moriendi

- Player-Versus-Player Campaigns

- How to Fill Out Your Character File

Genre and Tropes

The New Ars Moriendi is a superhero setting through and through, but it’s a grounded one. Drawing more from the likes of Worm or Invincible than Marvel or The Incredibles, this setting is one where the consequences of using powers are as important as the powers are. And while the power system is built around bringing back the dead as a central, universal mechanic, there’s a catch. People can come back with powers once, after dying without them. From there, matters of life and death do actually mean death when they say it.

The World You Know

This setting doesn’t start with a sweeping alternate history. There aren’t decades of backstory built in from the get-go, and while getting the exact details of real life nailed down isn’t the priority per se, calling on your own experience to make judgements about what the setting might be like is entirely reasonable. It’s encouraged, even.

Featuring Superpowers

The main difference is the zombie apocalypse, which is turning out fairly well, all things considered. Three years prior to the setting’s debut storyline (Miracle Girls), Lyn Marsh was fatally struck by a car and wandered out of the morgue into a life of fame as the first superhero, Extraordinaire. Since then, a steady stream of individuals with a second lease on life have been showing off more and more varied powers with less and less room for scientific explanations. Those with powers don’t outnumber the rest of humanity yet — not by a long shot. But they’re here, and that alone is making the future a much more interesting place.

What You Need To Play

To play a game of The New Ars Moriendi you need the Cortex Prime Game Handbook, the additional rules on this page, enough dice for each player and the GM (or a way to roll them digitally), and blank character files for each player. Also recommended are turn markers and blank notecards.

Cortex Prime Rules and Variants

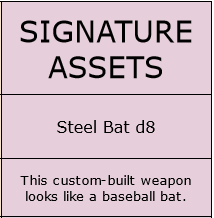

This setting uses three prime sets: attributes (Brawn, Motion, Wits, Research, Influence, and Composure), specialties (no skills, just specialties), and, of course, distinctions. Distinctions have the default “Hinder: Gain a PP when you switch out this distinction’s d8 for a d4″ SFX. In addition to the prime sets, powers are represented with the abilities mod, and signature assets may come and go as appropriate.

The New Ars Moriendi uses action-based resolution (often in an action order) instead of tests and contests and uses the doom pool for difficulty. Sometimes, that doom pool will be used to fuel crisis pools representing environmental threats, obstacles, or abnormally potent powers.

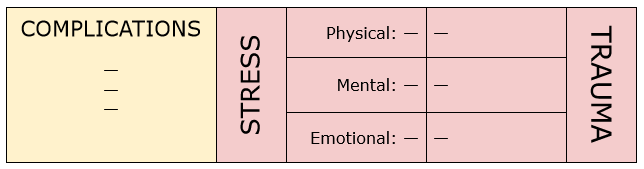

While complications (and assets) have their place, conflict resolution in a powered battle is generally going to come down to stress and trauma. You have the option of pushing stress, but don’t get too reckless during your adrenaline rush. The stress tracks are physical, mental, and emotional.

As a character learns from their experiences, they can reference their session records to cheat on plot point costs or spend those records to gain or improve traits.

Character Creation

Characters in The New Ars Moriendi are scratch-built using the following stages.

Brainstorm

Before anything, the group needs to decide what side they’re playing for.

- If you’re making a team of heroes, create characters that care about other people, want to do the right thing, or feel pressured to live up to specific ideals.

- If you’re making a team of villains, create characters with deep-seated flaws, selfish motives, or sufficient external reasons to take desperate action.

- If you’re running a player-versus-player game, create characters with conflicting goals, existing history that’s fraught with drama, or incompatible moral frameworks.

Determine your character’s personality and backstory. When in doubt, refer back to what you decided and make decisions based on that, more than anything. Connecting your character’s backstory to the backstory of at least one other player can help glue the party together when the story gets underway.

You’ll need a name, too.

Determine Distinctions

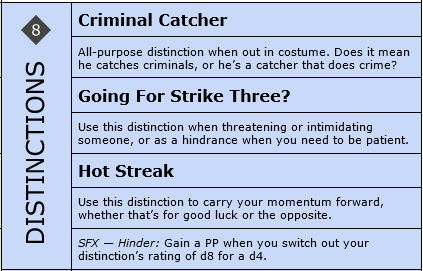

Once you know who your character is, boil down that concept into three core traits: your distinctions. These traits form a prime set, so they’ll be available for almost any roll.

For each of your three distinctions, give the d8 a name and the “Hinder: Gain a PP when you switch out this distinction’s d8 for a d4″ SFX. You can add a short description to the trait so you know when to use it, including as a hindrance.

Assign Attributes

With your character defined in narrative terms, it’s time to decide their strengths and weaknesses by adjusting the attribute array they’re using. Your attributes form a prime set, so they’ll be available for almost any roll.

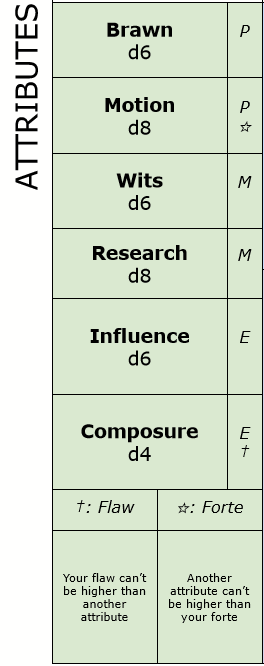

There are three categories with two attributes, for a total of six attributes. The categories are physical, mental, and emotional, and each correspond to a stress track.

- The physical attributes are Brawn (for raw muscle and athletic training) and Motion (for speed and agility, but also for steadiness and precision).

- The mental attributes are Wits (for quick thinking, resourcefulness, and problem-solving) and Research (for learnedness, study skills, or other access to information).

- The emotional attributes are Influence (for exerting social power and causing changes in the emotions of others) and Composure (for maintaining autonomy and resisting the Influence of others).

Every character (yes, even that unnamed extra) has a rating in Brawn, Motion, Wits, Research, Influence, and Composure. The default rating for each is d6.

When you create your character, pick one attribute to upgrade to d8, as a freebie. Then, you may step down any one attribute to step up a different attribute. If you do this, the attribute you stepped down is your Flaw, and the attribute you stepped up is your Forte. Flaws and Fortes have specific rules when being improved with session records. You may only have one Flaw and one Forte (even if you start with two d8 attributes — pick which one is your Forte and which one you just happen to be pretty good with).

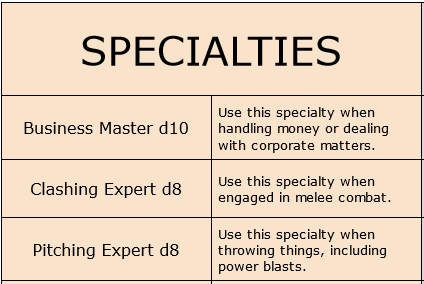

Select Specialties

To represent the things your character is good at, you’ll need to pick a few specialties. Your specialties form a prime set, so they’ll be available at all times even if the ones you picked don’t really apply to every roll.

You have four points to assign to specialties of your choice. A point creates a specialty at d8 (Expert) or steps it up to d10 (Master). You can spend one point on two d6 (Trainee) specialties, but it’s not recommended. d12 (Champion) specialties cannot be attained during character creation.

Any specialty you have can be replaced with X dice that are stepped down by X-1. For example, when firing a ranged weapon, you can roll a Sharpshooting Master specialty as a d10 (one die stepped down by zero), as 2d8 (two dice stepped down by one), or as 3d6 (three dice stepped down by two).

Anything can be a specialty. A non-exhaustive list might include Acrobatics, Arts & Crafts, Business, Clashing, Coercion, Crime, Diplomacy, Driving, Medicine, Performance, Science, Sharpshooting, Stealth, Tech, and Trivia.

Okay, Now Die (Your Powers Will Be Provided Shortly)

You’ve done a great job creating your character. Unfortunately, they don’t survive their backstory if you want to start the game with superpowers. So what happened? The specifics of the incident may provide secondary elements for your power and primary elements for shaking up the story (for instance, if you decide that you were murdered, your killer is liable to show up in the campaign at some point). [Suicide can never grant powers in this setting. I could explain the in-world justifications for that rule, but the root and final word are that the connotations of allowing that would not be acceptable to me.]

Now, your character won’t remember this, but they played a game at the gates of the afterlife, much in the same way that people once cheated Death with a chessboard and a whole lot of gumption. Death has stepped out for a while, and the person managing the games at the moment has raised the stakes a bit. What this means for you is that you need to pick a game and tell your GM what it is and how your character plays it with so much on the line. You don’t need to win. You’re just supposed to be interesting, and the game and your strategy are the primary inspiration for your power. In-setting, that’s true when the person running the games comes up with the power. Mechanically, it’s true when the GM writes your ability.

For example, Special Agent Allison Chains was killed in the line of duty shortly after joining the FBI, and she came back to life as the federal superhero Maiden America. Allison’s game of choice was Battleship. The bird’s-eye perspective of the game board inspired her power of flight, and the basic game action of firing missiles at spaces on the board inspired her power to sling fireworks.

Hand your character off to the GM. When you get them back, skip over the next section and pick up from the “Player Powers” heading.

GM Power Creation

As the GM, you have the option of running through the games your players chose with them before the campaign, if that’s what the group wants. Otherwise, just ask each of them for whatever details they can share about their character’s plan during their posthumous game.

When you create an ability for each player, your primary inspiration should be the game they picked and the strategic or tactical decisions made for the character during that game. Your secondary inspiration should be the circumstances of the character’s death. If you want to ask your players for more input, that input should be limited to your fallback inspiration. Use it when you’re stuck.

The core of the power should be rooted in your primary inspiration, while the flourishes can dip into your secondary inspiration. Define the narrative capabilities and flavor of the power first and foremost.

For example, say a character chose Twister as their game after drowning. Twister relies on flexibility and balance, so the power should improve those. Aesthetically, the power may or may not have something to do with water. If the character (Adam) focused mostly on staying in the game, they get defensive boosts. If they (Barb) tried to trip their opponent up, on the other hand, they’ll be better at attacking with their power.

To continue the example, both Adam and Barb end up with the ability to stretch their limbs. Adam, though, doesn’t get much in the way of reach. Instead, he can flare out his arms to create shields, intercepting attacks for his allies or reducing the severity of damage that comes his way. Barb, meanwhile, has more offensive capabilities. Her stretching is a rapid jab that partly liquefies the moving limb, striking with a hydraulic force from a respectable distance, but leaving herself open to a counterattack.

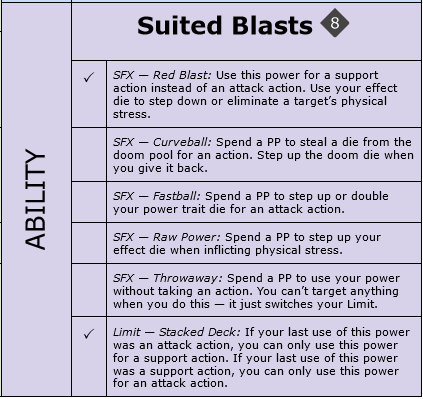

Once you’ve defined the power itself, codify its rules as an ability. It needs a power trait that starts at d8, an effect tag, the description you’ve already come up with, an optional limit, and a list of five SFX options.

To expand the example, the power trait for the Twister characters would be Stretching d8. Adam’s effect tag is Defense, while Barb’s is Attack. (The other effect tags are Sensory, Movement, Control, and Enhancement.) Barb’s power also has the “Guard Down: When you make an attack with this ability, your foe can let you gain a plot point to keep an effect die from their reaction” Limit. Adam’s list of SFX might pull from the Force Field and Regeneration abilities, while Barb’s SFX might pull from the Blast and Super Strength abilities. (These sample abilities are in the Prime Lists chapter of the Game Handbook.)

If you offer more than five SFX options, you might start the power at a d6 to offset the extra versatility. Conversely, if you can’t come up with five SFX options, you could start the power at a d10 (or you could pull from your fallback inspiration).

That’s all there is to it.

Player Powers

The ability you’ve received from your GM should have a d8 power trait and a list of five SFX attached to it. Include the power trait in your pool whenever your ability is contributing to the action or reaction you’re taking.

You don’t get all the SFX right away. Your character is slowly discovering their power, and the SFX in the list define what they might grow to be capable of as they master it. Pick one of the SFX options to unlock from the start. The rest can be added by spending session records.

Finishing Touches

Once you have your ability, your character is done!

Of course, you can add a little bit to the end of your character’s backstory if you want to skip past the earliest trial and error they put their powers through. Eventually, you’ll want an alias for your character’s costumed identity, if they assume one. Other than that, you’re ready for the game.

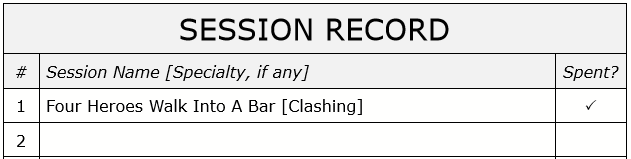

Growing Characters

The New Ars Moriendi uses the session callback system of character growth. To improve as a superhero or supervillain, you’ll need to learn from your mistakes and double down on your triumphs. At the end of each session, players give the session a name and write that down on their session record. Once per session, each unspent session in a session record can be used for a callback in place of spending a plot point. Sessions can also be spent from a session record for training.

Training Up

Here is a summary of the advancements and upgrades players might spend their sessions on. Note that no trait may be raised higher than d12.

- Turn an asset from a session into a signature asset: 1 session

- Switch out a distinction for a new one: 1 session

- Add an SFX to a signature asset that doesn’t have one: 1 session

- Step up a signature asset: 2 sessions

- Add a new specialty at d8 (Expert): 2 sessions

- Add a new specialty at d6 (Trainee): 1 session

- Step up a Trainee specialty to Expert: 1 session

- Step up an Expert specialty to Master: 3 sessions

- Step up a Master specialty to Champion: 4 sessions*

- Step up an attribute (to d10 at most): 4 sessions

- Your Flaw cannot be raised higher than your lowest non-Flaw attribute

- Non-Forte attributes cannot be raised higher than your Forte

- Your Forte can be stepped up to d12

- Unlock a new ability SFX: 2 sessions

- Step up an ability power trait: 3 sessions

*Champion specialties can’t be taken on a whim. To be a Champion at something is to be one of the best ever, and that’s something you have to prove. When you log a session in your session record, if a specialty of yours was important during the session, you can mark the session with that specialty. Only marked sessions can be spent on a Champion specialty, and only if they’re marked with that specialty. Marked sessions can still be spent normally as well. When your GM sees that you’re marking sessions with a specialty, they may decide to introduce a GMC that’s a Champion at that specialty for you to face off against.

GMCs

The New Ars Moriendi may use all the rules available for GMCs.

- If a character has superpowers and a position of power, they should be a major GMC.

- If a character has superpowers or a position of power but not both, they should be a minor GMC.

- If a character is a recurring or stable ally of the players, they should be a minor GMC unless they fulfill the qualifications to be a major GMC.

- Power-affected zones or other noteworthy areas can be location GMCs (or they can be a crisis pool).

- Henchpeople can be extras on their own or mobs when met in bulk.

- Very strong opponents or powers that take the form of what would otherwise be a character can use the rules for bosses.

- Whenever necessary, throw a few extras into the scene.

- As the players make a name for themselves, they should encounter factions and orgs of various dispositions. Given time and access to resources, they could even manage one.

Running The New Ars Moriendi

Serial storytelling is the lifeblood of The New Ars Moriendi, but the setting can be tuned for a more episodic approach fairly easily. As with superhero comics, a single issue may work best as part of an ongoing story arc, but if it can also stand on its own perfectly well, that’s even better. And the same goes for standalone story arcs stacking up into one grand narrative. That said, don’t plan too far ahead just yet.

Your First Session

On the GM side of the matter, what you’ll bring to the first session is a city built to host the game, either at first or for the entire story. Set up the factions in power, the context the players are running headlong into, and the level of action that’s typical for the area. If the players are significantly more dramatic than that typical level of action, they’ll attract enough attention to propel the game as a series of reactive situations. Otherwise, give yourself enough elements to tap into later whenever the game threatens to hit a lull.

If the players didn’t form or join an existing team as part of character creation, then the main goal of session one is to introduce everyone and plant the idea that they’ll be seeing much more of each other as time goes on. A bank robbery is responded to by several independent heroes at once, and they have to learn how to avoid stepping on each other’s toes if a similar scenario comes up in the near future. A few criminals with powers are approached by a mysterious contact, who offers to make it worth their while if they’re willing to play ball for now. So on and so forth.

The first session doesn’t have to end with some sappy speech where the characters all agree that the power of friendship will overcome all odds, and if it does, someone in the speech’s audience should probably make fun of the person talking. Still, the circumstances at the start of the campaign are the ones that will lead to these characters becoming one functional team in the face of whatever obstacles you present them with in their new roles.

Hero Campaigns

There are always new villains popping up that need to be investigated, and old villains are always hatching new schemes that need to be thwarted. A hero party can sit back and react to what’s going on around them, running from mission to mission and protecting people from various threats. Even a runaway train or a burning building (represented by crisis pools) can draw the attention of a hero team for the first session or for an adventure later on.

Maintain a rogue’s gallery for the game that you can refer back to when the players need to face a new challenge. You can track the status of each villain (at large, in hiding, imprisoned, or otherwise) and change that status when you’ve got spare doom dice to throw around. Recurring antagonists help tie the game together, and they can serve as a benchmark for progress if an early-game challenge returns without something new to compensate for the heroes’ improvements. If a villain is out for revenge, of course, they may rear their head with plenty of improvements of their own.

For a more proactive hero campaign, a team that rallies around a specific cause or forms in response to an active investigation will have to go after the chosen goal rather than simply wait for assorted crimes to occur. This only really lasts for the one storyline, though, so the players should plant their own ideas for follow-up missions before they complete the one they’re already on.

Villain Campaigns

A villain campaign is often more work for the players, and it may or may not be more work for the GM as well. The villains are expected to be proactive, since sitting around and waiting for something to happen isn’t really a crime. The variety in the game will arise as the players come up with new plots or respond to new information in their own ways.

That said, keep things fresh in the setting itself without making the players do all the work. If they face the same heroes over and over, constantly coming out on top, those heroes may lose public confidence and open the door for replacements to move in on the territory. Speaking of territory, being a team of villains in no way means the party is safe from other villains, and they may have to contend with rival gangs, deal with unreliable allies, and respond to other threats to whatever position they’re trying to carve out for themselves.

For a more reactive villain game, consider creating a team of mercenaries. The steady flow of mission requests allows the GM to come up with the situations, and lets the players simply pick up or reject each story hook. Of course, turning down a job may open the door for more villainous clients to move from incentive to extortion, so they’ll have to watch out.

What Happens Next?

Hero or villain, the party is in a world that’s always moving. The fallout of any given conflict may be felt entire arcs down the line if you play your cards right, and what’s been happening is always what informs what’s going to happen. Maybe you set up a particularly long-term antagonist in the first few sessions, or maybe you want a clean break between one arc and the next, but either way, there’s going to be more story to tell. You just need to find it.

And if you need help with that, here are some jumping-off points that can invigorate a game that’s hit some downtime:

- An upstart hero team is making their debut, with no respect for matters of jurisdiction

- A bit of information the characters would prefer to keep secret has leaked, and the recipient has demands

- Partway through a murder investigation, the victim wakes up and can’t control their new powers

- A group of dangerous, superpowered vagrants turn up on the edge of the city the campaign is currently set in

- An internal schism in another group occurs, and the splinter groups start looking for ways to prove themselves

Player-Versus-Player Campaigns

The conflict between heroes and villains is the drum that beats in the background of all storylines in this setting. It takes the spotlight every so often, and it informs the rest of what’s happening in the narrative. If you want to bring this conflict to a more central position in your game, you can place player characters on both sides of it, forcing the two (or more) groups to form an uneasy alliance or contend for victory at the others’ expense.

One-Shots

This scenario is tricky to balance long-term. One solution to that problem is avoiding it entirely, and only running one scenario with the characters that were made to face off.

In a one-shot scenario, the characters and their goals have already been defined. The villain team wants to lift a priceless painting from the museum, and the hero team is called in to stop them. The hero team is gearing up to raid a local crime den, and the villains need to defend their territory. Whatever the case may be, this game isn’t about the long road that led to this confrontation. If the players want to get right into the action, then bring the action!

Waiting around for your turn is especially bothersome when the players aren’t working toward the same goals. To ensure that both sides of the fight have fun, the reactive players need to get a chance to respond as early as possible. At most, give the active players one bridge scene to establish the stakes before the reactive players kick down the door and interrupt them.

The active players are the characters who have a specific goal. The reactive players are the characters who want to prevent the active players from succeeding.

If both sides have independent goals or share a goal, it’s even more important to get everyone in play from the get-go. Some heroes working a press conference that have to drop everything to stop a heist aren’t just trying to fight the villains to a standstill, they’re going to have to look good for the camera while they do it. If two rival gangs are racing to find a double-agent that’s gone rogue, the villains sent to handle the search might team up for a while, then betray the alliance once the target’s in sight. Whatever the case may be, start the session when the characters come across each other — don’t give one side a scene to take the advantage first.

If you want to keep these characters around for later one-shots, feel free to introduce escape routes for the losing side. Give the heroes top-of-the-line medical attention, and maybe a medal or two. Flash forward a week and have the news mention a local jail break. End the session with the promise that both sides are back on their feet for the inevitable grudge match that will follow. If you don’t plan to run another one-shot, though, wrap the story up before the session is over! The fate of each character, particularly on the losing side, should be given the weight it deserves. The winning side, meanwhile, might be looking to leverage the rep boost for new recruits (thus, giving the other players a perfect way to introduce their new characters and launch a campaign where everyone’s on the same team).

Your First Session

If you’re picking up a game that started as a one-shot, then guess what? You’re done. Skip to the next section. But for a game that’s intending to run for the long haul with a split party, the first session exists to set up the major factions in this conflict. Your rival parties might not even cross paths until halfway through the game, so you need to be sure that both sides are getting adequate individual attention.

Your first session might even be your first two sessions, as you’re free to run separate games for each set of players. In this case, refer back to the strategies for a normal campaign, and incorporate the advancements one set of players makes into the prep for the next situation the other set has to deal with.

A Balancing Act

A long-term game where the players are opposing each other has to be managed in a way that keeps the outcome in doubt. Employ the rule of drama: whenever things are going too smoothly for one set of players, throw a wrench in part of their plan. That said, the goal of this game is to work toward a climactic final showdown, and that can’t happen if one side collapses under its own weight before the finish line is in sight. GMC threats are liable to be merciful when they come out ahead, or distracted and redirected before they get the chance. These threats are complicating variables, not boss fights. They’re here to slow the conflict down and keep it going, not stop it. If it takes a lucky break to avoid taking one side of the conflict out of the fight, then be good luck.

Where Does This All Lead?

The characters for a game like this one should have been made with goals in mind, and those goals should stand in the way of each other in some manner. Those goals are the endgame, the signpost at the end of the road. The intersection is where you set your finale.

The confrontation between your heroes and your villains (or whatever factions you’re playing against each other) can take many forms and can end many ways. There’s nothing wrong with a good old-fashioned final battle, with the losing side taken out of the picture for good. That said, it’s worth considering other ways to end the game over the course of one or more sessions:

- A tense negotiation between the warring factions, determining whether a compromise or ceasefire is possible and erupting into a brawl only if things are pushed past the breaking point

- A dramatic courtroom showdown where the side that’s on the back foot has one last chance to turn things around and come out on top

- The arrival of an external threat to both factions, which forces them to cooperate or risk both goals failing to come to fruition (this same threat may change the context of the story to make the conflicting goals simultaneously possible as a reward for setting aside the characters’ differences, or it may just lend a tragic element of “what could have been” to the real final confrontation)

How to Fill Out Your Character File

Here is an example of a filled-out character file for a powered individual, and below are explanations of the steps and choices made.

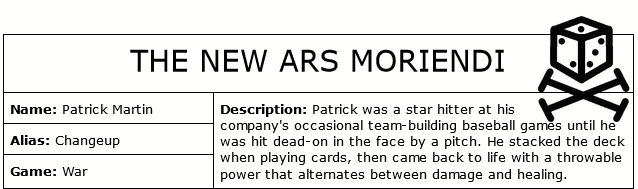

1: The first thing to define and write down about the character is who they are in a narrative sense. This example is Patrick Martin, a hobby baseball player who dies when a jealous colleague goes a little too aggressive during a game. Based on the choices to play a card game called War and to stack the deck for his own victory, the GM decides to give Patrick a power that operates as a stacked deck in its own way, firing black energy blasts to dish out damage and red ones that undo it, and never the same color twice in a row. Given this power, Patrick picks the name Changeup (a pitch type and a reference to his power’s mechanics) for his costumed identity.

2: All attributes start at d6. As a freebie, one steps up to d8, and Patrick picks Research to represent his skill in the office and his tendency to count cards.

Next, Patrick picks a flaw and a forte. As a baseball player, Motion is the attribute that best represents accuracy in pitching and hitting and speed on the bases. It gets stepped up by one and marked with a ☆.

Composure is Patrick’s flaw, because he’s a go-with-the-flow type employee with a bit of a temper. The attribute gets stepped down by one and marked with a †.

3: Three short, snappy distinctions are the next step, and descriptions of how to use them come in handy. These distinctions can be anything. For Patrick, these ended up being a mix of baseball puns and gambling allusions. All distinctions come with the basic Hinder SFX already unlocked.

4: Four points go into specialties, with each point unlocking or stepping up a d8 (Expert) specialty. Patrick unlocks Business, Clashing, and Pitching to make sure he’s good at his day job, holding his own in a brawl, and firing the blasts from his power. Since Business is the specialty he’d have the most practice in, it takes the last point and steps up to Master. Short descriptions help remind you when to use each specialty.

5: With all of that wrapped up, the GM creates the ability that represents Patrick’s power. The power trait is Suited Blasts, ensuring the name makes sense for both uses of the power, and it starts as a d8.

The GM includes a limit to represent the way the power switches between attack and support, so that comes with the ability from the start of the game.

Five options for SFX are also included with the ability, but they aren’t all available yet. Patrick chooses one to start with, and since the power doesn’t work properly without providing a way to heal allies, picking Red Blast is a given. More can be unlocked by spending the sessions that Patrick plays through.

6: For the sake of the example, Changeup gets to run through an imaginary session and it’s added to the session record. Since the opening story was a superpowered bar fight, the session is named appropriately and the specialty for fighting in close quarters is marked as important. Patrick decides to spend the session on a signature asset.

7: To make sure he was ready for a fight, Patrick called on his business connections to have a thematically appropriate weapon made before going out in costume. Rolling with his specialty let him create the asset during the session, and spending the session let him keep it around afterward. His d8 effect die was a better return on that investment than the d6 he’d get just by spending a plot point.

8: This space left intentionally blank. The character file is ready for use.